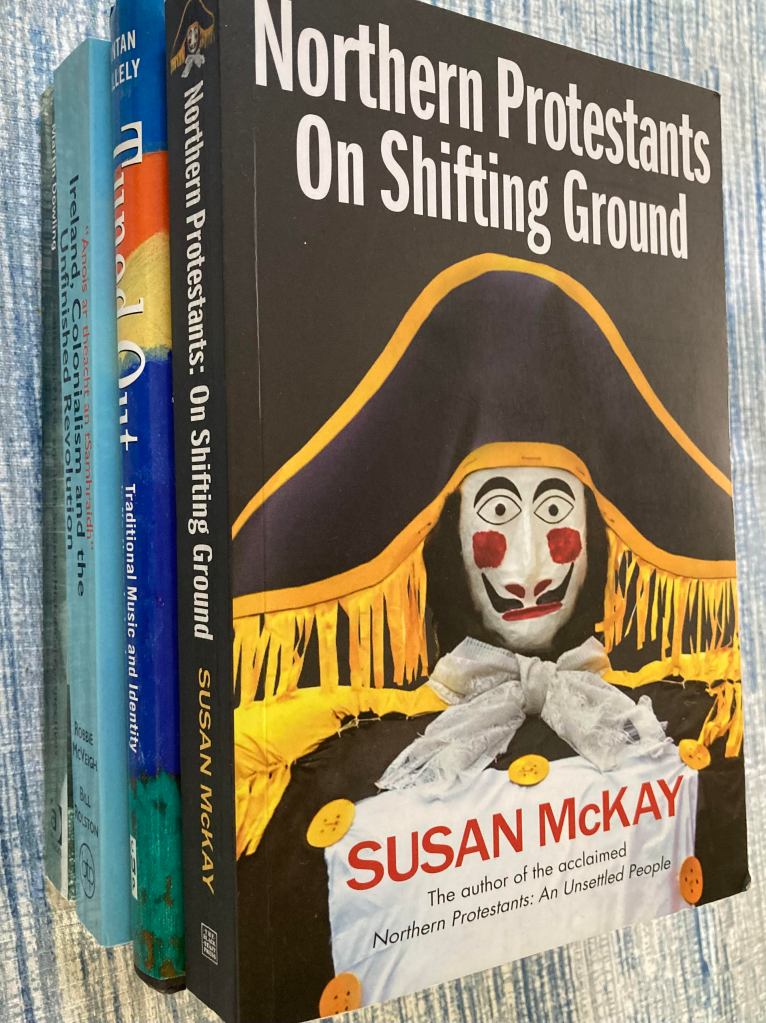

In Nostalgia for the Light, the powerful meditation on memory and trauma by Chilean film maker, Patricio Guzman, an astronomer states that the present is, at best, a fleeting entity. Everything comes with a delay, however minute. We are always dealing with the past and in some places, like Chile and Northern Ireland, this struggle is very visible and often confounding. One book that has clarified some questions for me is Northern Protestants On Shifting Ground by Susan McKay. I have not read a more eye-opening and heart-wrenching book in a long time.

This book is required reading for all, at home or abroad, who espouse romantic wishes for Irish unity. I count myself among them. And while distance makes the heart grow fonder, it can and should, also bring a more critical and comparative perspective. (Every Irish immigrant has been asked more than once to explain the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland: it is usually an unsatisfactory experience all round.)

McKay cuts right through the rigid politics and blustering binaries that often infest policy discussions about Northern Ireland. The major myth the book explores is that there are two monolithic, irreconcilable sides in the Northern Irish story, one Protestant, loyalist and unionist and the other Catholic, republican and nationalist. A careful look at the history of the Northern statelet would indicate that it was never so but the ruling Protestant majority nurtured that supremacist illusion for almost 50 years in Northern Ireland.

The revelations come thick and fast. Prepare to be schooled on the wide range of perspectives, values and opinions held by people who embrace the term unionist, often without the big U. McKay seeks out people from Protestant backgrounds, like herself. We hear from many women, feminists and otherwise. From a range of LGBTQ Protestants. From Unionists who fear any form of United Ireland and unionists who, surprisingly, would accept that outcome if that was how a referendum played out.

There are socialists, activists, community organizers, and local elected representatives. A revealing number of her interviewees come from mixed backgrounds, are married to Catholics, or have Catholics in their extended families. Kenneth Branagh’s heartfelt film, Belfast, is set in a mixed residential neighborhood before the violence drove everyone back into sectarian enclaves.

McKay speaks with a number of artists who offer wide-ranging, open-minded and hopeful perspectives on the way forward. Colin Davidson is a painter who created an exhibit called Silent Testimony that was widely seen in the North. He speaks about people’s reaction to his paintings of survivors of the violence:

People went in and were struck by the fact they weren’t told who the Protestants and Catholics were, and some of them said to me they were ashamed at themselves for even thinking they needed to know. That actually goes to the very heart of what the enduring problem in this place is. We still haven’t got over the “them and us.” In fact, I wonder if we’ve even scratched the surface.

Stacy Gregg is a playwright and filmmaker who says, “a lot of my identity has straddled binaries: gender, nationality, class.” She attended Cambridge where she became painfully aware of her working class status.

You can’t grow up here and not be political. I’m very aware that Protestants don’t get a good rap. I feel uneasy when people mock working-class Protestants -it shows a poverty of empathy.

But she also comments on the waning of Protestant privilege:

I think most of that protestant privilege is essentially gone or going, but the residual entitlement remains, and can become brittle or defensive. So this bizarre Protestant entitlement helps me understand why some behave as they do.

An Irish language revival has been underway in the North for some years primarily in nationalist areas. The official use of the Irish language has been championed by Sinn Fein and is bitterly opposed by many Unionists. The real story is more nuanced. The fastest-growing group of Irish language learners in the North are Protestants. Linda Ervine runs an Irish language school, Turas (Journey), in East Belfast and speaks about the long history of Irish-speaking Protestants, something which I was sadly ignorant about:

We are steeped in this language. Protestants who reject it don’t know their history. Catholics who claim it as their own don’t know it either. Language doesn’t vote, doesn’t sectarianise, doesn’t fly a flag.

And, with a nod to the book’s cover image of the effigy of “Traitor” Robert Lundy that is burned annually in Derry, scholar Sophie Long says she accomplished a Full Lundy by learning Irish in England.

Jan Carson, author of the acclaimed novel The Fire Starters, is grateful for her upbringing enriched with biblical language and stories. But she is critical of how reductionist the church teachings have become.

I’m interested in an inscrutable God. That’s how the church has failed artists over and over again, because it’s not about the unknown and it should be. Instead the model of the church is corporate worship, for we all sing the same thing at the same time. Artists want to play and think and work outside the box.

And Pamela Denison, a Protestant businesswoman from Antrim, believes the churches were to blame for their decline.

I think religion can be dangerous, very dangerous. I’m not anti-Protestant. I’m just anti-religion.That is how they were reared, a lot of people can’t see past the end of their own lanes. They haven’t opened their minds to other cultures and ideas.

The paucity of politics among loyalists is highlighted. One interviewee calls it geriatric politics, with its singular focus on slogans like No Surrender and What We Have We Hold. Dawn Purvis, from the progressive Unionist party, pinpoints the barrenness:

Northern Ireland for the British. What does it mean? What does it mean when that happens for people who hold onto this notion of identity that they can’t explain, but it is something that they hold onto, like somebody’s trying to steal it from them.

The book also explores the differences between Protestants and Catholics in higher education and career pursuits. Queens University in Belfast is described as a “cold house for Unionists” since Catholic students are the majority and exhibit a stronger drive for educational advancement. Younger Protestants often leave to study in British universities and don’t return. This is considered a grievous generational loss.

History gets a nationalistic spin in most countries. I was taught Irish history by a rabidly republican Kerryman: Britain never did anything right in 700 years of occupying Ireland and propped up the sectarian statelet in the North. The Irish, heroically, never did any wrong. It’s an old story. Even Theobald Wolfe Tone, a hero and martyr of the 1798 rebellion, admitted that hatred of England was always “an instinct rather than a principle.” It’s still being taught with a slant. My 10-year old granddaughter completed a class assignment on The Troubles at her parochial school in South Dublin last year. She came home with this revelation: Protestants were the bad guys here.

The book is a set of interviews with a wide range of Northern Irish unionists and Protestants conducted between 2019 and 2021 and a sequel to her earlier book, Northern Protestants: An Unsettled People. It’s an ethnographic tour-de-force with journalistic flourishes. Many of the segments, pithily headlined, open with the words of the interviewee, some are almost entirely quotes from the person’s testimony. McKay only intervenes to contextualize key events or provide some history for violence or atrocities from the “Troubles” for general readers.

The place of Unionists in some form of a United Ireland (United Island? New Ireland?) has been front and center in the public conversation especially since the passage of Brexit. Andrew Trimble, a retired Irish rugby star, offered his argument in a recent interview in the Irish Times. Rugby people should be heard since it is the one major sports that resisted division after partition and always fielded an All-Ireland team.

Any talk of uniting Ireland must explore this set of fundamental questions. How are the Unionist Protestants accommodated? How do you learn to accept a somewhat unlovable crowd, people who are not just British or Irish but their own awkward selves as Michael Longley put it? What kind of neighbors would they be? How do you avoid creating a “cold house” for them in the new arrangement? And, for some Sinn Fein supporters, how do you resist the temptation to include payback for years of running a vicious, sectarian statelet?

The book offers satisfying answers to those questions. Many of the interviewees come across as sound, thoughtful, and reliable persons. They would be good neighbors, resourceful in an emergency, and respecters of boundaries. The politics and religious attitudes of some would be hard to live with but the present-day Republic is a more diverse, multicultural and tolerant community. The Reverend Ian Paisley’s old jibe about the South being ruled by Rome seems utterly outdated now. One interviewee notes that a unified Ireland would work out all right in the end but the 10-20 years it took to get there could be hellish.

One way or another, Catholics, Protestants and Dissenters (largely from the Presbyterian tradition) have been interacting and cohabiting in those six counties for hundreds of years. Now a critical point has been reached where the dissenters of various persuasions are edging out the unionist and republican extremes, as Emma de Souza argues recently in the Irish Times. Young people have moved away from traditional religious affiliations making the Catholic-Protestant binary more irrelevant than ever. The elections coming up in May will reveal the strength of the center and how likely it is to hold.

It’s time to stop the “Othering” of groups of people that has plagued Northern Ireland and many places in the world. The present is fleeting but also immensely fragile. Politics everywhere cannot be simply local when the effects of climate change are omnipresent and poised over our future like a tsunami. Fighting over power and control in a small corner of the world is futile, foolish, feeble and wasteful.