Dublin can be heaven if you are seeking cultural stimulation, and the Hodges Figgis’ bookshop is a good place to look. In June, I was fortunate to be there for the book launch of Camarade by my friend, Theo Dorgan. The audience was studded with poets, writers, scholars, musicians, and sundry cognoscenti: I was perhaps the most anonymous attendee. I sat next to a distinguished-looking gentleman with a lilting Northern accent. We chatted amiably, but initially I did not catch his name.

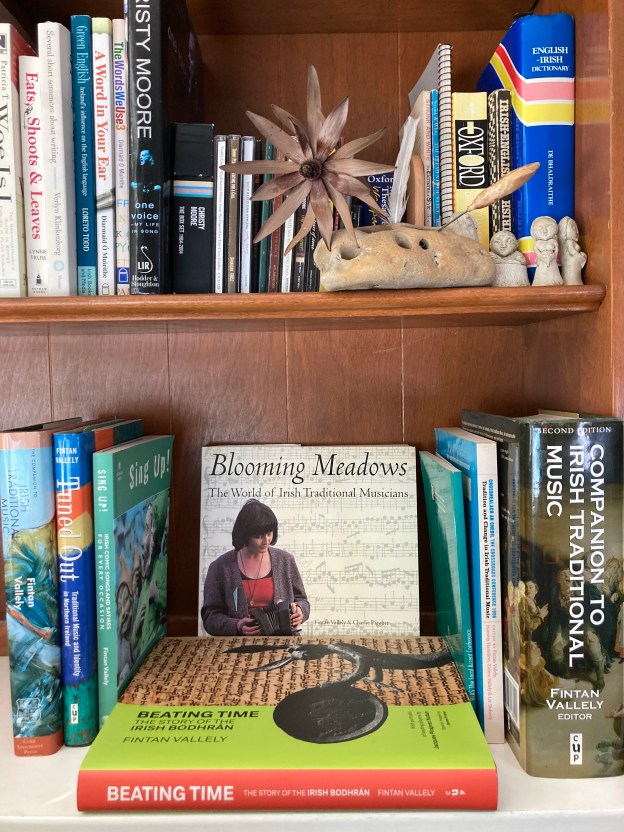

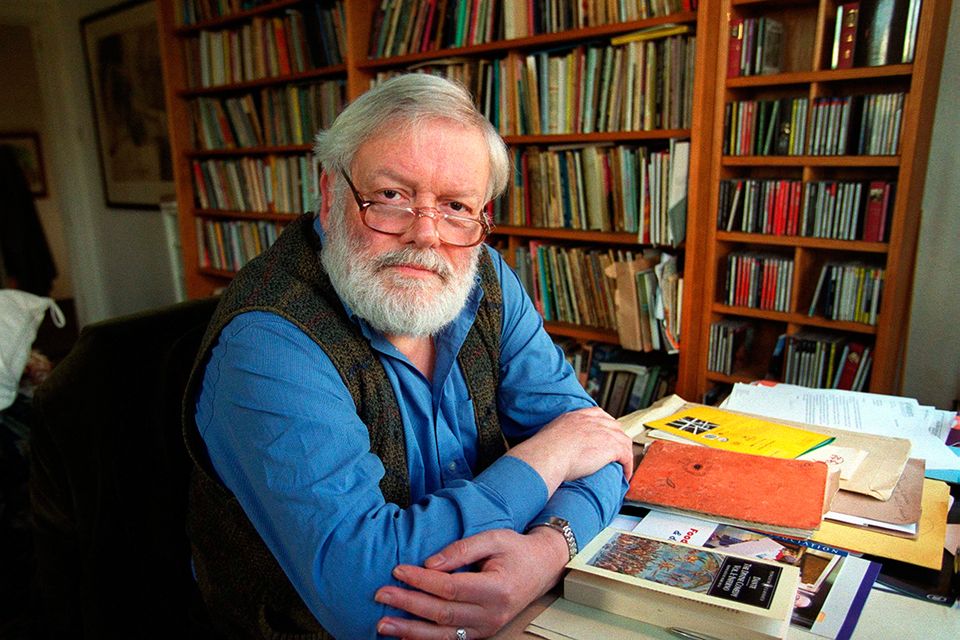

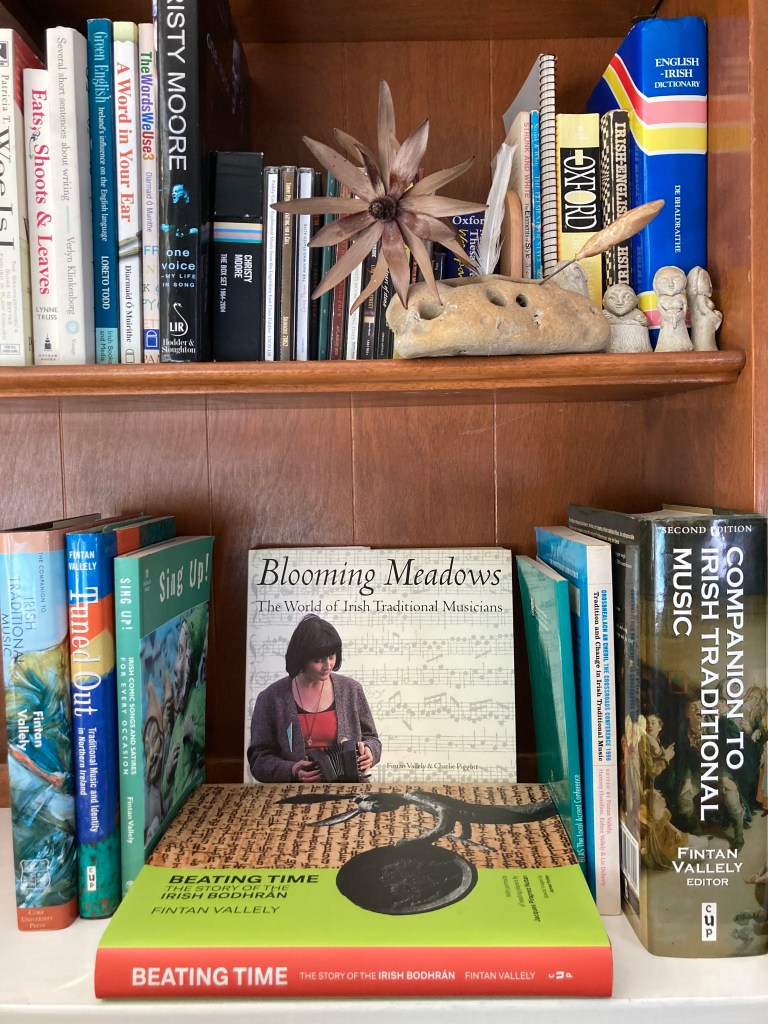

Imagine my astonishment, then, when I realized I was talking with Fintan Vallely, Ireland’s preeminent expert on Irish traditional music and a highly accomplished flute player. He has been writing, speaking, teaching, and advocating for traditional music for over fifty years. I have a decent collection of his writing, suitably curated in the title photograph. I have relied upon his books and articles as sources of sound information (especially the series of Companion Guides), stimulation, and writing inspiration.

His newest book, Beating Time: The Story of the Irish Bodhrán, explores the history of Ireland’s favored percussion instrument. The frame drum is not nearly as old as many people think. Vallely dates its high-profile arrival in Irish music to 1959, when it featured in the music for Sive, John B. Keane’s play, at the Abbey Theater. Sean O’Riada was the Abbey’s music director, and he was drawn to the drum’s possibilities. He made room for a bodhran player, Peadar Mercier, when he created a new ensemble, “ceili” band, Ceoltóirí Chualann (“The Band that Changed the Course of Irish Music”) in 1961.

The new book features vivid portraits by Jacques Piraprez Nutan and James Fraher and an extraordinary array of archival material, photos, and illustrations. Vallely establishes the tambourine as the origin of the drum. There is little evidence that it was present or necessary historically in the deeply melodic traditions of Irish music, Vallely asserts. However, improvised drums were fashioned from frames used for winnowing and sifting, particularly by Wrenboys on St. Stephen’s Day.

His book is suffused with organic intelligence. There are no artificial ingredients. Every chapter is rigorously researched, carefully arranged and annotated, and beautifully presented. The writing smoothly weaves dazzling details into the larger narrative. He is a Master collaborator. Each edition of the Companion guides involves contributions from dozens of musicians and music scholars. He is generous in his credits and acknowledgements and wears his erudition lightly.

Nicholas Carolan, former Director of the Irish Traditional Music Archive, introduced Vallely’s book at the Willie Clancy Summer School this July. He said Vallely had tirelessly researched the bodhran for many years and drew from a great range of recently digitized information. “He’s produced here both a definitive history of the Irish drum, and also an exemplar, a template for writing the social and musical history of other instruments of Irish traditional music.” On that last point, the concertina would be an excellent topic.

My favorite among Vallely’s works is Blooming Meadows, The World of Irish Traditional Musicians, a book of 30 interviews and portraits of Irish musicians published in 1998. Co-written with Charlie Piggott and featuring Nutan’s photographs and a “borrowed’ bar stool, the book is a treasure of lore and legends. The timely book offered a wealth of stories on long-established musicians, including Joe Burke, Ann Conroy, Paddy Canny, Joe Cooley, Lucy Farr, and Ben Lennon. It features many others who were on the cusp of greater recognition: Martin Hayes, Sharon Shannon, Liz Carroll, and Brendan Begley, among others. The format of short essays paired with a good image was one inspiration for my blog when I started it in 2008.

His other works in my collection are Tuned Out, a comprehensive and authoritative (like all Vallely’s writing) exploration drawn from interviews with musicians of how Irish traditional music fell out of favor with many Northern Protestants, regrettable collateral damage in the political polarization wrought by The Troubles. Sing Up is a humorous, clever collection of Irish comic and satirical songs. It’s got a whole section called Goatery and Percussion with songs about the bodhran.

Arguing at the Crossroads goes back to 1997 with ten essays on a changing Ireland. Vallely’s essay surveyed the state of Irish music at that point (post-Riverdance) and found it in rude health. The Local Accent, Selected Proceedings from BLAS also dates from 1997, and includes his provocative essay, The Migrant, the Tourist, the Voyeur, the Leprechaun. Vallely edited Crosbhealach An Cheoil (The Crossroads Conference, 1996) with Hammy Hamilton, Eithne Vallely & Liz Doherty.

Vallely is a walking/talking encyclopedia of Irish traditional music. In our brief conversation at the book launch, he summarized the key points of his bodhran research, mentioned his studies of The Princess Grace Song-Sheet Collection in Monaco (an astounding piece of catalogue work), and described the evolution of the Third Companion Guide into recordings on CD and DVD. He also gave me a copy of his 2021 CD, Merrijig Creek, an enchanting album of his compositions and arrangements with a powerhouse set of musical partners: his sister, Sheena, on flute, Caoimhin Vallely, their cousin, on piano, Liz Doherty and Gerry O’Connor on fiddles, Daithi Sproule on guitar, and Brian Morrissey on, you guessed it, the bodhran.

Vallely is an ubiquitous presence in the Irish music literature. I like to think of him as a key “influencer” before it was a popular or profitable role. Beating Time has everything you would want to know about the bodhran (including brass tacks) and much more that you may find intriguing and enlightening.

Links and additional sources:

All of Vallely’s prodigious work, books, recordings, articles, and other musical projects can be found at his website imusic.ie:

Irish arts suffered a tremendous loss this month with the untimely death of Sean Rocks, the voice of arts coverage on Irish radio for 20 years. Here are two short clips from his RTE programme, Arena:

First, an interview with Fintan Vallely about Beating Time.

https://www.rte.ie/radio/radio1/clips/22533245/

And, second, Sean Rocks interview with Theo Dorgan discussing his new novel, Camarade.