A review of Shared Notes: A musical journey by Martin Hayes

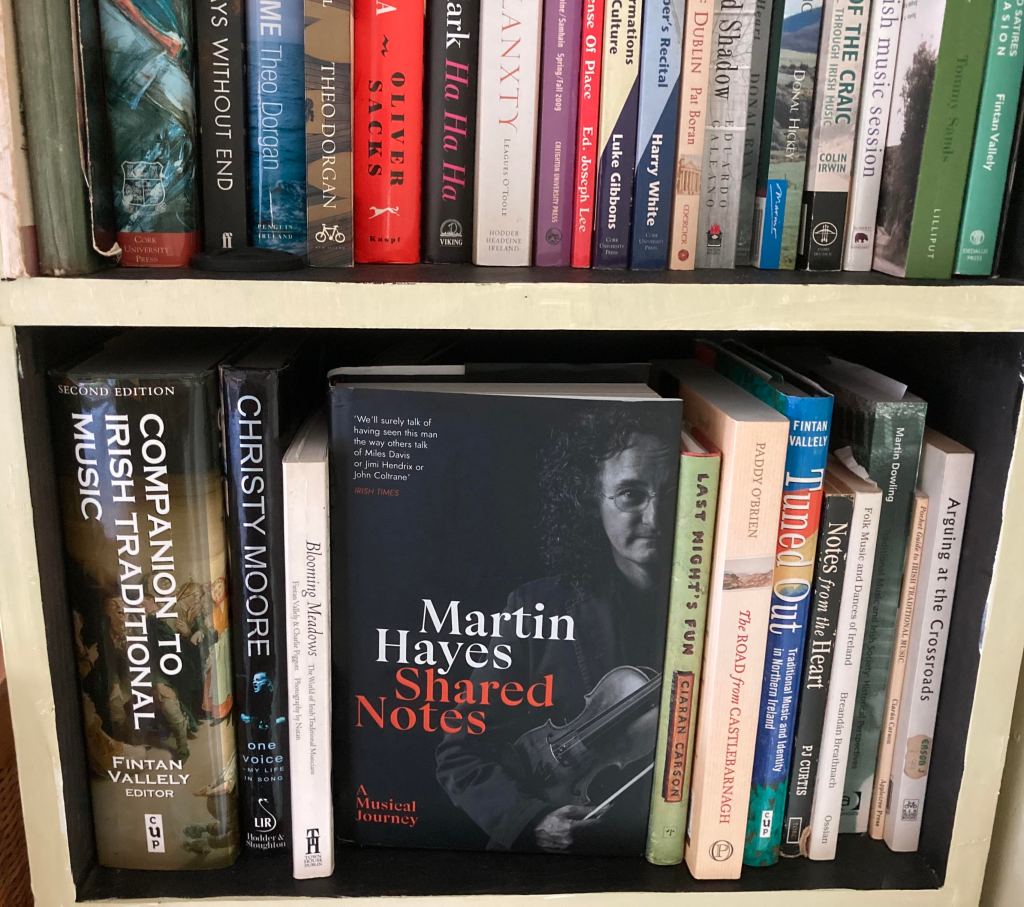

Martin Hayes has written a memoir that’s every bit as brilliant, engaging and moving as one of his famous extended performance sets. The Irish fiddle player was forced onto the sidelines by the Covid epidemic in 2020 but that gave him the time and space to complete the book. In his music, he’s a master of time and space and those skills transfer to the flow, structure, and measured pace of the narrative. It’s a substantial and welcome addition to the meager store of good books on Irish music. The photograph shows a selection from my own modest collection with Hayes’ book in pride of place.

His story starts in the heart of a hotbed of traditional music in East Clare. He grew up immersed in that culture working on the family farm, walking to and from school, and absorbing the music organically along with its “doctrine of soulfulness.” Hayes opens with a lovely portrait of his mother who was “an independent-minded, free-thinking spirit.” She had worked as a nurse in the psychiatric hospital in Ennis and as a waitress in an upscale restaurant in London. She had also spent a year training to become a nun, something Hayes did not learn about until his father’s death in 2001. Irish mothers can diligently secure their secrets. She only lasted a year in the convent, emerging with a lifelong suspicion of authority and a watchful eye for hypocrisy.

Like mothers in many traditional cultures, she gave up her ambitions and dreams to nurture and tend to her husband and family. Not to mention feeding the steady stream of musical visitors who came to commune with Martin’s father, PJ Hayes, leader of the famed Tulla Céilí Band. His father was a huge influence on him but he had other sound ancestors like his uncle, Paddy Canny and local fiddler and piper Martin Rochford. Other early musical influences included Tommy Potts, Joe Cooley, Tommy Peoples, Peadar O’Loughlin, Junior Crehan and Tony Mac Mahon.

Hayes has a number of aphorisms that he regularly delivers with style and precision. One of them is, “… the 1970s were the 60s in Ireland.” More sociologically sound than it seems on the surface, Hayes was a teenager in the late 70s so he knows whereof he speaks. Early on, he was a conforming non-conformist, a position that many young Irish people began to adopt in that era. He worried that he was, “… a socially compliant cultural manikin at the cost of a normal teenage life.”

But, wanted or not, social change was coming to rural Ireland in the 1970-80s and Hayes, like many others, took off for elsewhere. He is unsparing in describing the ups and downs of his life journey. He was enamored of the drink for a few years but giving it up brought more clarity and focus to his search for meaning. He ended up for a time living illegally under the radar in Chicago on an expired tourist visa, suffering the embarrassment of being ripped off by a shyster immigration attorney when he tried to become a legal resident. He had his fallings-out with fellow musicians and once smashed his fiddle on the head of band member.

His detailed and loving memories of childhood and adolescence are extraordinary. The book covers the paths not taken. At various points Hayes could have been lost to music by becoming a Fianna Fail political figure or a frozen food salesman or, briefly, a stock market trader in Chicago, or even a college graduate with a business degree (he dropped out after a year.) And his musical journey had some unproductive byways. Like playing banjo for a time in the Tulla Céilí Band, or playing an electric fiddle in a Chicago folk-rock band, Midnight Court, or accompanying ballad singers in a bar band.

At one concert, Hayes has had enough of the audience members who talk and drink noisily during the show. He asks them to leave, offers a refund, and they reluctantly depart. It’s an empowering moment when he exercises his right, with righteous anger, as a performer to play in conditions that suit his musical goals and ambitions.

Hayes has done the work to arrive at an authentic self and a workable philosophy of life. He came through a tough period when he felt he was losing his past, was disengaged from the present, and not creating a future. His personal spiritual search brought him back to the music. Integrity for any musician or artist is complicated, Hayes says, and “Sometimes, we’re just not ready to handle our own gifts.” He writes eloquently about his experiences teaching music where he revels in the mutual learning possibilities in that creative exchange.

He is deeply committed to making his music “invitational,” drawing the audience into emotional participation, a reciprocity that can be transcendent. Many older musicians frowned upon stage craft but Hayes found that he had to grapple with the dynamics of performance to bring his playing up to the highest possible levels.

Hayes is the preeminent exponent of Irish traditional music in the world. He has transcended his status as an Irish fiddler to achieve parity with other artists, classical and otherwise, in concert halls far beyond Ireland’s borders. He plays, “Music in the universal sense first, and Irish music second.” And performing in more formal settings brings its share of stress. Since traditional musicians don’t usually read music, playing extended pieces with an orchestra can produce a unique kind of terror and sense of inadequacy. Hayes describes this clearly in the book and it matches the experience that Tony Mac Mahon endured in his first performance with the Kronos Quartet.

He brings a high degree of artistic, intellectual and cultural credibility to Irish music, universally defined. Hayes was fortunate to have a long line of ancestors, many with musical abilities. In turn, he has become a good ancestor, taking the long view back and into the future. He is a master practitioner with the right blend of character, charisma and modesty for younger players to emulate. He has done a great deal to expand and enrich Ireland’s cultural capital as a musician himself and as a facilitator of combinations that have led Irish music into new pastures.

In the first post on this blog in 2008, Hayes and Cahill: Recalibrating the tradition, I concluded: “This is quantum music played with a bonsai sensibility, centrifugal explorations of notes and the spaces in between, pulsing with possibility.” Hayes observes that particular notes in tunes carry more weight than others. In Shared Notes, he weighs his words and deploys them as artfully as he draws out the ancient melodies.

Martin Hayes annotated Blogiography

I was fortunate to hear and see and, in time, talk with Hayes as his playing career ascended the heights. Here’s a collection of blog posts on Martin Hayes. He has been a source of great inspiration for my writing over the years. My first piece on Hayes in the San Francisco Irish Herald in September, 2000, was titled Zen and the Art of Fiddle Playing. I first heard him at the San Francisco Celtic Music Festival held each spring for ten years from 1991 under the watchful eye and ear of the late Eddie Stack.

https://theoldblognode.blogspot.com/2018/08/fiddling-on-dock-of-bay-review-from.html

Later, in that same timeframe, I heard him play in various combinations at the Sebastopol Celtic Music which was guided by Cloud Moss. His book honors the memory of those festivals as seminal influences in his playing career. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Hayes made regular appearances in the San Francisco Bay Area. He savored the spaciousness and freedom he experienced in the city and felt that the spirit of Joe Cooley was still in residence.

https://theoldblognode.blogspot.com/2008/10/hayes-and-cahill-recalibrating.html

There was something very fitting about seeing Hayes and Cahill play in church buildings around the area. Apart from the acoustics, the settings induced a certain reverential expectation that was often fulfilled.

https://theoldblognode.blogspot.com/2011/10/hayes-and-cahill-at-skyland-church.html

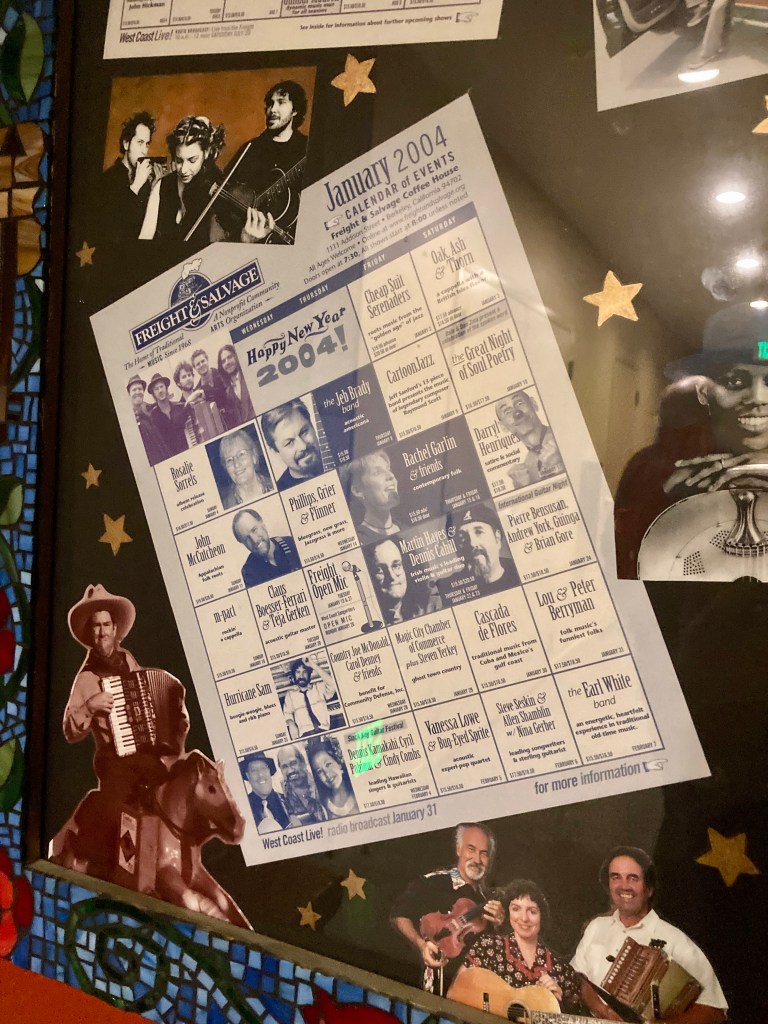

Hayes played many times at the legendary Berkeley concert venue, the Freight and Salvage. One of his appearances with Dennis Cahill from 2004 is recorded on the venue’s calendar wall.

One unique evening is recorded here when sound engineer Tesser Call facilitated an acoustic miracle.

https://theoldblognode.blogspot.com/2012/03/hayes-and-cahill-break-sound-barrier-at.html

Hayes brought every one of his musical groups to Berkeley: twice with The Gloaming, once with his Blue Room Quartet, and once with Masters of the Tradition. Every show was memorable and magical. The two Gloaming concerts are reviewed here:

https://theoldblognode.blogspot.com/2014/12/roaming-with-gloaming-in-berkeley.html

https://theoldblognode.blogspot.com/2017/10/the-gloaming-returns-to-berkeley.html

And the mesmerizing evening with Hayes’ Quartet playing their Blue Room album is reviewed here:

https://theoldblognode.blogspot.com/2018/10/quadruple-delights-from-martin-hayes.html

And here are two insightful reviews of Hayes’ memoir by fellow-fiddle players, Niamh Ni Charra in the Irish Times and Toner Quinn in the Journal of Music.

Lovely, Tom. No, brilliant. Your love for the music shows so well in your writing. Very moving.

I sent this to Brenda Malloy who lives in Dublin and is American born. And plays the Irish harp and love Irish music.

Hope to see you and the MISSUS soon

Jeff

>

LikeLike